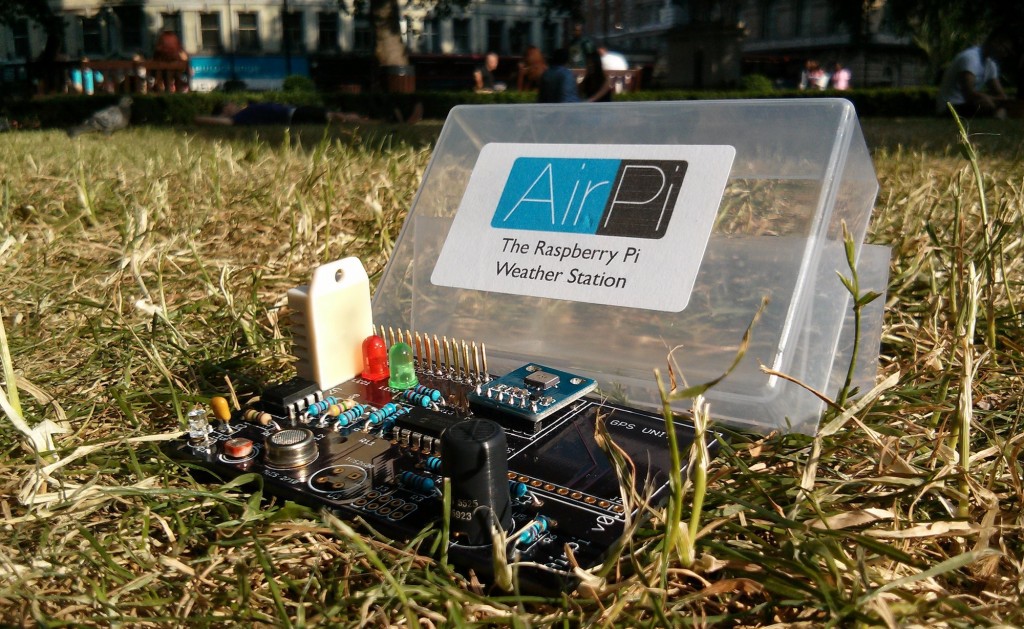

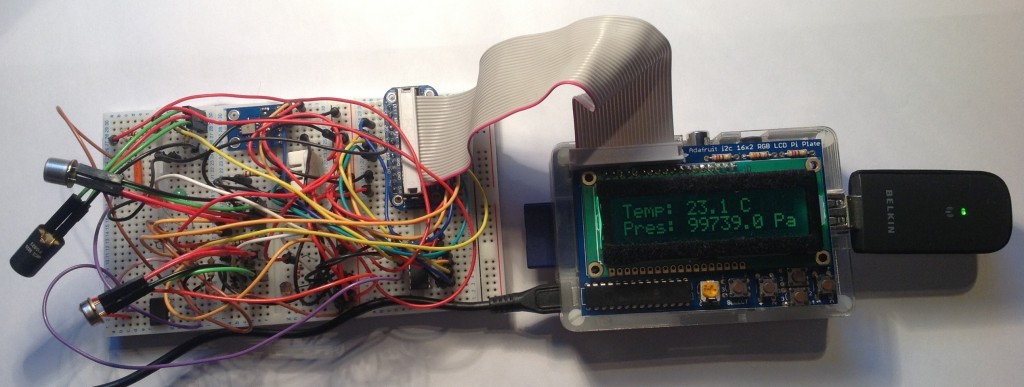

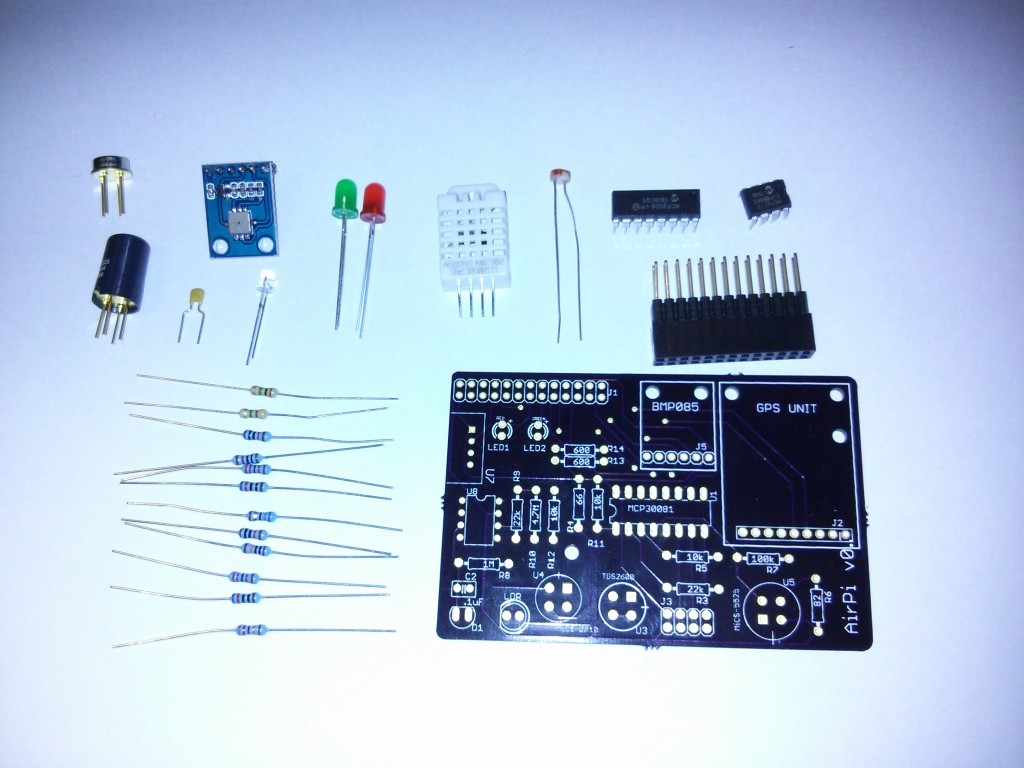

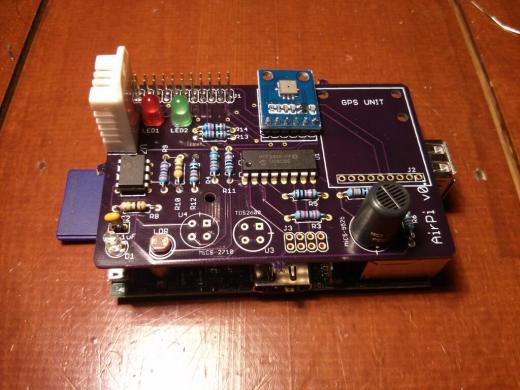

| Liz: When Clive and I are asked what schools project in the past year has really knocked our socks off, our response is usually the AirPi, an inexpensive pollution and weather monitor developed by Alyssa Dayan and Tom Hartley, a pair of sixth formers from Westminster School in London. AirPi won the PA Consulting Raspberry Pi competition earlier this year, where entries had to “make the world a better place”, and we regularly use it in talks as an example of the amazing things that can be achieved with a Pi and some ingenuity. AirPi is an open-source weather and pollution monitoring system, with the ability to record and stream data. Including the Pi, it comes in at £55: tens of times cheaper than equivalent off-the-shelf equipment. Things have come a long way since the first, competition-winning iteration of AirPi: Alyssa and Tom have been learning about PCB design and entrepreneurship and have just launched a Tindie to raise funds to sell the kit. I’ve asked them to write about what they’ve been doing, and what progress they’ve made with AirPi over the last few months. Here’s what Tom had to say: For the last 10 months, I've been working with Alyssa Dayan to create the AirPi. Its a shield for the Raspberry Pi capable of recording data about the air quality and current weather conditions, coupled with code to upload its recordings to the internet in real time. Just last week, we started a fundraiser for our kit on Tindie! The project started back in October 2012, when one of our teachers (we're both sixth form students) told us about the PA Consulting Raspberry Pi competition. The challenge was to create something, using a Pi, which would "make the world a better place". We didn’t have a very clear idea of what to design, so we looked at the different kinds of hardware we could connect to the Pi. After checking Adafruit's website, we discovered a vast assortment of sensors, many of which measured meteorological information. Over the next 4 months, we purchased and added on various parts from all over the world (testing and calibrating as we went along), starting with the DHT22 which measured temperature and humidity, and finishing with the UVI-01 which measures UV levels. That was the very first incarnation of the AirPi. Simultaneous to developing the hardware, we started developing the software. It was split up into Python scripts (which are currently undergoing a complete rewrite!) running on the Pi, and a live updating website (with HTML5 websockets!). By February, we'd started putting basic instructions on how to make your own AirPi onto our website (this was a stipulation of the competition), and one of the most incredible moments we had was when an awesome guy from the UK, Paul, emailed us and said he'd already put one together. Before that point we had no idea that people would actually be interested in building an AirPi themselves! In March, we were invited to the finals of the competition. After polishing up our website and tidying our breadboard (above), we headed to PA Consulting's offices near Royston. We started by getting a tour around, and seeing the awesome workshop and labs that PA had. In the afternoon we were judged the winners in our category. After the event was over, the project gained some interest online, and about 10 other people have put an AirPi together by hand since then. Of special note however, was Taylor Jones, an electronics engineer in the US, who emailed us saying he wanted to design a PCB for the AirPi. I have now started learning that dark art, but at the time neither I nor Alyssa had any experience making PCBs so we were incredibly glad to have his help! After three iterations, we had a functional PCB – this made the AirPi much more compact and easy to assemble, so we decided to start making kits for it. We signed up for a stand the Elephant & Castle Mini Maker Faire - this was brilliant as it gave us a fixed date we had to get the kits ready by. After reinvesting the prize money from the PA consulting competition into components, PCBs, packaging and stickers, we were ready to head off to the Maker Faire with the kits. We sold out of all 15 kits we had purchased for the day! In the weeks after the Faire, we were contacted by several very awesome groups of people: a new green initiative in Ho Chi Minh city in Vietnam has purchased three kits in order to measure the air quality there, and the Chaos Computer Club in Germany has bought 15 in order to teach children to solder. We've even had several archivists in the UK who've asked us to give them some so they can accurately monitor the temperature and humidity of the books they're looking after! In the near future, we're hoping to develop a 3D printed case for the AirPi which will allow people to put it outside a lot easier. After many requests for a kit, we've started a fundraiser on Tindie (sort of like a Kickstarter, but especially for electronics). If you're interested in ordering a kit to measure temperature, humidity, UV, NO2, CO, light and air pressure for £55, then you can go to this page - we’ll be shipping them out in late September. Alternatively, we have published all the source code, instructions, components needed and even the PCB files and schematics online, so if you want make and assemble one yourself (or improve upon our design), feel free to do so. We love open source – without the amazing work of so many people online, there could be no AirPi. If you build one, we'd love to hear from you and add it to our website. Thank you for reading! |

A Semi-automated Technology Roundup Provided by Linebaugh Public Library IT Staff | techblog.linebaugh.org

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

AirPi – the next step

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment